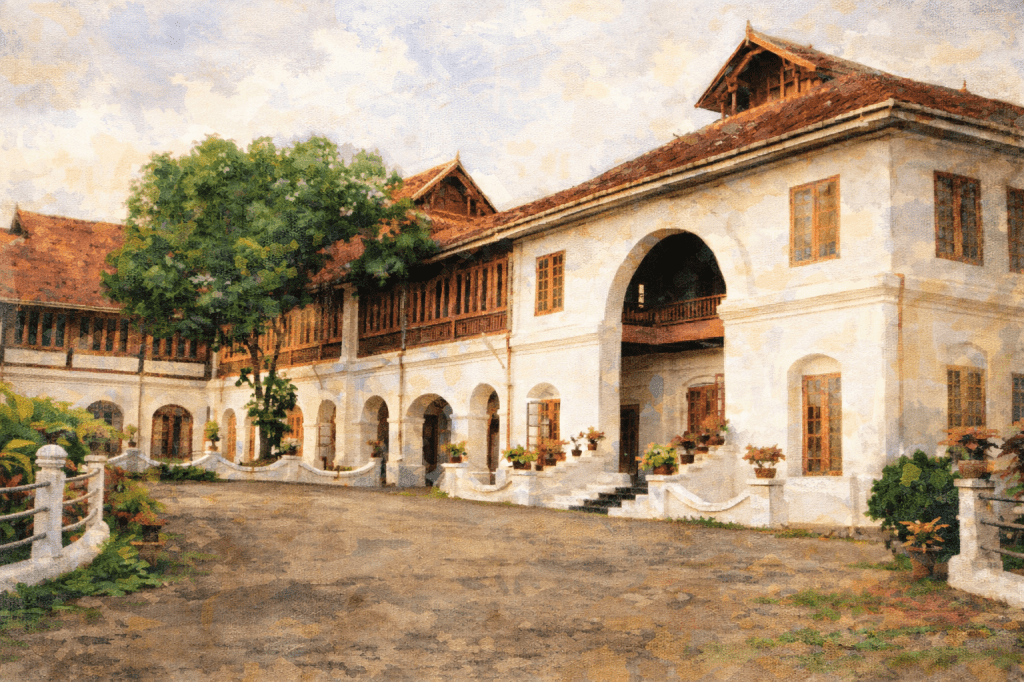

Perched on a quiet hillock far from the bustle of town lies one of Kerala’s grandest heritage treasures, a sprawling palace complex built in 1865 that now stands as the state’s largest archaeological museum called the Hill Palace. Spread across an impressive campus of 49 traditional buildings, the complex is a world of its own, complete with a children’s park and even a deer park nestled within its leafy grounds.

For any history lover, this museum is a journey through centuries. Its 13 galleries showcase everything from Indus Valley artifacts to royal heirlooms, mural art, bronze and wooden sculptures, palanquins, antique weapons, oil paintings, and rare gifts exchanged between rulers. Yet the most captivating charm lies in the buildings themselves, elegant structures crafted in pure Kerala architecture, echoing the legacy of Cochin’s royal lineage.

At the centre of this vast complex stands the Royal Mansion, the earliest structure, believed to be completed in 1855 by Cochin Raja Ravi Varma. Its grand ettukettu architecture which is two nalukettu courtyards joined by exquisite wooden corridors & reflects the opulence of a family that once shaped the history of Cochin. Inside, the cabinet room steals the spotlight with an antique lift imported from England, Victorian wall tiles, ornamental metalwork, Italian marble flooring, and beautifully patterned ceramic tiles inside the royal chambers.

As you walk through the courtyards and connected wings such as the Poomukham, Ootupura, Akathalam, Thevarapura, and Madapally, each corner reveals another layer of the palace’s story. Together, they narrate the rise of the Perumpadappu Swaroopam, the Cochin dynasty believed to be descendants of the ancient Perumals.

Their journey was far from simple. Forced to move south with the rise of the Zamorins in the 13th century, the Cochin rulers eventually reclaimed Chitrakoodam in the 17th century, where a coronation was planned. But when the Zamorin invaded and halted the ceremony, the Raja took a solemn vow never to wear the crown until crowned at Chitrakoodam. Remarkably, none of his descendants wore the crown, and today it rests uncrowned in the museum topped with dazzling jewels, a silent testament to a royal oath never fulfilled.

The mid-18th century was a turbulent chapter in the history of Kochi, a time when the shifting sands of power transformed the political landscape of Kerala forever. At the heart of this upheaval stood the visionary and formidable ruler of Travancore, Marthanda Varma, whose ambition and military genius reshaped the destiny of the region.

By the 1740s, Marthanda Varma had already begun expanding his kingdom with remarkable speed. He deftly used Kochi’s internal rivalries to his advantage—supporting factions within the royal household, forging temporary alliances, and subtly weakening the principality from within. His strategic interference, combined with the looming threat of annexation, pushed Kochi into the arms of the Dutch East India Company, who were themselves eager to preserve their influence on the Malabar Coast.

What followed was a dramatic confrontation known as the Travancore–Dutch War (1739–1753). Though the Dutch initially posed a formidable challenge, Marthanda Varma’s disciplined army and relentless strategies proved decisive. The turning point came with the monumental Battle of Colachel in 1753, where the Dutch suffered a crushing defeat, the first major loss of a European naval power to an Indian kingdom. This victory not only cemented Travancore’s supremacy but also marked the beginning of the Dutch decline in Kerala.

In the decades that followed, Kochi’s political world shifted irreversibly. Though the kingdom retained its name and royal lineage, it gradually became a tributary state, functioning under the towering shadow of Travancore. This altered political reality deeply influenced Kochi’s administrative and architectural evolution—including the fate of the now-famous Hill Palace.

During the reign of Rama Varma XV of Kochi, the region witnessed renewed building activity, possibly driven by a desire to reassert cultural identity and political dignity in an era dominated by Travancore’s power. It is plausible that the construction or expansion of the Hill Palace was inspired by the grand palaces, courtly residences, and administrative complexes rising in Travancore at the time. As Travancore modernized its governance and built imposing architectural symbols of its authority, Kochi too sought to create a seat of power that reflected its royal heritage, resilience, and enduring sovereignty—even if diminished.

With the arrival of the Portuguese, Dutch, and later the British, Cochin flourished into a major port, gaining wealth and global significance. One of its greatest rulers was Rama Varma Shakthan Thampuran, whose 18th-century reforms shaped the administration, markets, and cultural legacy of the region.

Exploring the palace grounds feels like stepping into a royal panorama with terraced walkways, fountains, manicured gardens, and sweeping views from the hillock. It’s no surprise that many iconic films have chosen these corridors as their backdrop.

Today, maintained by the Department of Archaeology, the palace complex stands as a spectacular blend of history, architecture, and culture — a place where every visitor finds something to marvel at. Whether you love heritage, art, photography, or simply wandering through beautiful spaces, this palace is a journey you will carry with you long after you leave.

Leave a comment