Kerala is a land where history reveals itself not only through chronicles and battles, but through the quiet elegance of palaces that once housed powerful rulers and nurtured art, culture, and craftsmanship. Among these architectural treasures, Krishnapuram Palace stands out as a rare and refined example of traditional Kerala architecture blended with royal grandeur. Located at Kayamkulam, this palace today functions as a museum under the supervision of the Archaeological Department of Kerala and is officially protected as a historical monument. While its architecture is impressive, the soul of Krishnapuram Palace lies in its murals especially the monumental Gajendra Moksham, one of the finest mural paintings in Kerala.

The origins of the palace trace back to the rulers of Odanad (Kayamkulam), though the exact age of the earliest structure remains uncertain. The original royal residence was destroyed after the defeat of the Kayamkulam rulers in the historic war of 1746, when the kingdom was annexed by Travancore under Anizham Thirunal Marthanda Varma. Following this annexation, a new palace was commissioned. The earliest Travancore structure was a modest single-storeyed ettukettu with a large pond, constructed under the guidance of the Travancore administration.

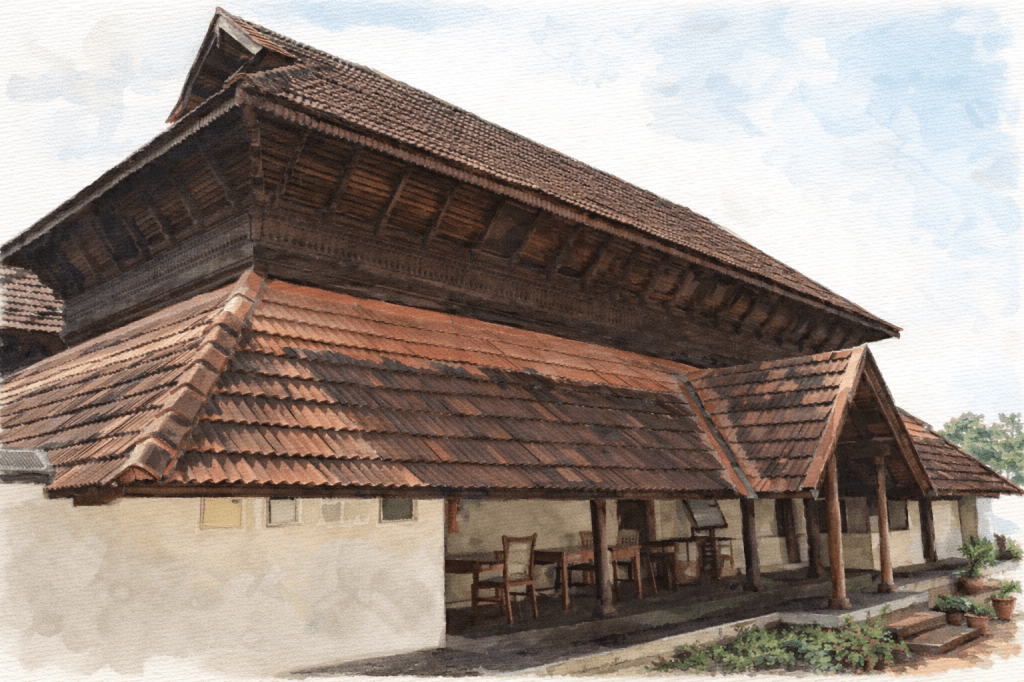

It was during the tenure of the renowned Prime Minister Ramayyan Dalawa that the palace rose to its present magnificence. Completed in 1764 after nearly three years of construction, the palace was rebuilt with an architectural vision that harmonised Kerala traditions with subtle Western influences. Gabled roofs, thick wooden doors, narrow corridors, dormer windows, and elaborate ceilings defined its form. Over time, the palace expanded into a pathinarukettu, a complex of sixteen structures arranged around four open courtyards (nadumuttam), showcasing the pinnacle of indigenous architectural planning. The lower tier of the palace contains twenty-two rooms of varying sizes, a graceful poomukham (entrance portico), a nellara for storing food grains, and a vast madappally (royal kitchen). The upper level housed the manthrasala, guest chambers, and royal bedrooms. Ingeniously designed stone drainage pipes, still functional today, highlight the engineering excellence of the builders. In its prime, Krishnapuram Palace would have rivalled the grandeur of Padmanabhapuram Palace, the famed seat of the Travancore kings.

Yet, architecture alone does not define Krishnapuram Palace. Its greatest artistic treasure is the celebrated mural Gajendra Moksham, painted over three metres high and positioned prominently at the palace entrance facing the pond. Believed to date back to the period of the Odanad rulers, this mural was preserved with reverence even during the Travancore reconstruction, reflecting its immense cultural value. The mural narrates a powerful episode from the Bhagavata Purana. The Pandyan king Indradyumna, cursed by sage Agastya, is reborn as Gajendra, the king of elephants. While bathing in a pond with his consorts, Gajendra is seized by a crocodile and trapped in a prolonged struggle. In despair, he surrenders to Lord Vishnu, invoking his divine grace. Moved by his devotee’s unwavering faith, Lord Vishnu arrives on Garuda, slays the crocodile, and grants moksha to Gajendra. This entire episode unfolds vividly in the mural through the masterful use of natural vegetable pigments. Garuda dominates the centre in fierce dynamism, while Lord Vishnu radiates calm divinity. Gajendra, depicted in surrender, contrasts with the violent grip of the crocodile. Surrounding figures include celestial beings, saints, animals, mythical creatures, and the elephant’s consorts. A striking and unique element is the depiction of child Krishna with female figures at the base an artistic liberty that adds depth and narrative richness. The mural’s placement ensured that it was the first sight the king encountered after his daily rituals, reinforcing the spiritual ethos of rulership.

By the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the palace fell into neglect as the Travancore kings shifted their administrative centre to Thiruvananthapuram. Exposure to monsoon rains led to structural decay. After Travancore’s integration into the Indian Union, the Archaeological Department undertook extensive restoration. Using traditional vastu principles and authentic materials such as laterite stone, teakwood, Mangalore tiles, red oxide flooring, and granite steps, the palace was carefully revived. Additions like spiral staircases and sunshades enhanced both functionality and aesthetics, while the palace footprint was reduced to strengthen the compound. In 1961, Krishnapuram Palace was formally converted into a museum. Today, it houses priceless artefacts that reflect Kerala’s royal and cultural history. Among them are the famed Kayamkulam vaal, a rare double-edged sword; a Sanskrit-script Holy Bible; the shield of Raja Kesavadas; and the Anchal Petti, one of India’s earliest postal boxes introduced in 1729. Within the palace grounds also stands a mandapam sheltering a Buddha statue one of the four discovered in Kayamkulam, believed to have been displaced during Kerala’s anti-Buddhist phase.

Today, Krishnapuram Palace stands as a profound reminder of a time when rulers valued art, architecture, and craftsmanship as expressions of civilisation itself. More than a historical monument, it is a living gallery where walls speak through murals, corridors echo royal footsteps, and history unfolds in colour and stone. To visit Krishnapuram Palace is not merely to witness the past, but to understand how art and history together shaped the cultural identity of Kerala.

Leave a comment