At the very heart of Thiruvananthapuram, a city celebrated for its royal legacy and cultural refinement stands a monument that has quietly watched history unfold for nearly two centuries. The Napier Museum is not just a museum; it is an architectural statement, a cultural classroom, and a social space that continues to shape the identity of Kerala’s capital. What makes the Napier Museum truly exceptional is its absolute uniqueness. There is no other structure like it anywhere in India. Rising gracefully within the sprawling zoo complex which is home to India’s first planned zoo, the museum seems to belong to multiple worlds at once. For travellers and history enthusiasts, a visit here is not merely about viewing artefacts, but about understanding how a progressive kingdom imagined art, knowledge, and public space long before such ideas became commonplace.

The vision for a museum in Travancore was first conceived by Uthram Thirunal Marthanda Varma in 1855. A modest museum opened to the public two years later, but as the collection grew in richness and scale, the need for a grander structure became evident. This ambition was fully realised during the reign of Ayilyam Thirunal Rama Varma, a ruler deeply committed to encouraging art, craft, and intellectual pursuit. His intention was bold to create a museum that would not only preserve heritage, but also inspire artists and attract global attention. To achieve this, Ayilyam Thirunal sought expertise beyond local conventions. On the advice of Lord Napier, the project was entrusted in 1872 to Robert Chisholm, the consulting architect of Madras. Chisholm’s ideas were radical for their time. Rejecting rigid stylistic boundaries, he proposed a daring Indo-Saracenic design that blended traditional Kerala architecture with Gothic, Islamic, Chinese, and modern European elements. Initially viewed with skepticism by the Travancore elite, Chisholm patiently explained how such a fusion would elevate local art and give Travancore an international architectural identity. Convincing the court was no easy task, but once approved, construction began in earnest. The project took eight years to complete. Delays arose from the demolition of the old museum, the careful relocation of artefacts to Kuthiramalika Palace, and the challenge of sourcing skilled artisans capable of executing such an unconventional design. Finally, in 1880, the Napier Museum opened its doors to the public as an instant landmark.

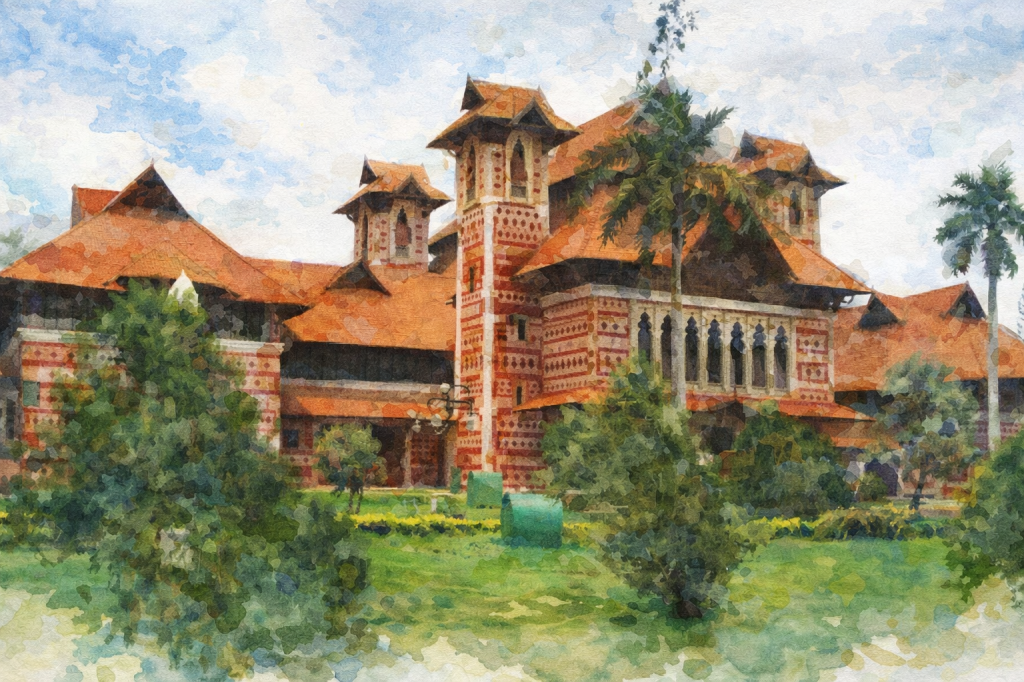

Architecturally, the museum is a visual feast. Set upon a raised pedestal with stairways on all sides, it commands attention from every angle. Minarets, towers, terracotta-tiled roofs, patterned brickwork, and vibrant colour palettes come together in perfect harmony. Chinese-style pagoda roofs lend the building a grandeur that exceeds its actual scale, while the reddish hue of burnt brick walls contrasts beautifully with the surrounding greenery. The central hall is flanked by four stone towers, each once serving as a lookout point over the city echoing the watchtowers of ancient forts. Inside, the brilliance continues. The museum’s famed double-wall construction ensures natural ventilation, keeping the interiors remarkably cool even during humid summers. Vast halls connected by long corridors painted in blue, yellow, and red house priceless collections without visual obstruction. Ornately carved wooden ceilings, hand-painted tiles, spiral staircases tucked discreetly into corners, stained-glass windows, Chinese dragon stuccos, Mughal-inspired motifs, and Gothic arches coexist effortlessly. Dominating the interior is the emblem of the Travancore kingdom, the Valampiri Shanku carved prominently, asserting the museum’s royal authority and purpose.

The collections housed within are as diverse as the architecture itself. Visitors encounter wood carvings, bronze sculptures, stone images, ivory masterpieces, metal lamps, coins, musical instruments, Kathakali models, and Japanese leather shadow puppets. Among the most arresting artefacts is the sword of Velu Thampi Dalawa, an early martyr of India’s freedom struggle. Once presented to Rajendra Prasad, the sword was later placed in the museum, where it greets visitors at the entrance as a powerful symbol of resistance and sacrifice. Equally fascinating is the Pushpaka Vimana used by Swathi Thirunal Rama Varma, and the colossal five-tiered wooden temple ratha, intricately carved with scenes from the Mahabharata and Bhagavatham. The bronze gallery is Kerala’s first of its kind that features rare and complete icons dating from the Pallava, Chola, and Vijayanagara periods, including an exquisite early bronze image of Lord Vishnu. The stone gallery spans centuries, from Dravidian and Buddhist traditions to later temple sculptures, with the figure of Sage Agastya standing out prominently. Ivory carvings, though displayed with modern sensitivity, showcase exceptional craftsmanship. The delicate Radheshyam carving of Krishna and Radha and serene images of Buddha are among the most admired. The South East Asian Gallery, dedicated to artefacts associated with Balarama Varma, highlights Travancore’s historic connections with Asia. Japanese shadow puppets, household objects, musical instruments, and a curated numismatic collection further enrich the experience. In all, the museum houses around 550 artefacts, each telling a story of art, belief, and exchange.

For nearly 150 years, the Napier Museum has remained woven into the cultural fabric of Thiruvananthapuram. Today, it is as much a place of leisure as it is of learning where families stroll, children discover history, artists find inspiration, and travellers pause to absorb the elegance of a bygone era. More than a monument, the Napier Museum is a living symbol of Travancore’s enlightened vision, standing proudly among the most iconic heritage structures of Kerala.

Leave a comment